Capillaria is a genus of parasitic roundworms  that infects chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese, grouse, quails, pheasants, guinea fowls and other domestic and wild birds. They belong to the group of hairworms or threadworms,

that infects chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese, grouse, quails, pheasants, guinea fowls and other domestic and wild birds. They belong to the group of hairworms or threadworms,

They occur worldwide and are very common in chicken: up to 60% of a population can be infected.

There are hundreds of species worldwide, although many species are nowadays assigned to other genera (e.g. Eucoleus, Aonchotheca, etc.). The most relevant species for poultry are:

- Capillaria annulata = Eucoleus annulatus, found mainly in chicken, turkey and wild gallinaceans in Europe, America and Asia.

- Capillaria bursata = Aonchotheca bursata, found mainly in chicken, turkey, pheasants in Europe and America.

- Capillaria contorta = Eucoleus contortus, found mainly in ducks, geese, nut also in chicken, turkey and many wild birds, worldwide.

- Capillaria caudinflata = Aonchotheca caudinflata, found mainly in chicken, turkey, geese, pigeons and many wild birds in Europe, Asia and America.

- Capillaria obsignata, found mainly in chicken, turkey, geese, pigeons and many wild birds, worldwide.

- Capillaria anatis = Capillaria retusa, found mainly in ducks, geese, but also chicken and turkey, worldwide.

These worms do not affect dogs, cats, cattle sheep, goats or swine. Other Capillaria species infect dogs and cats.

The disease caused by Capillaria worms is called capillariasis or capillariosis.

Are birds infected with Capillaria worms contagious for humans?

- NO: The reason is that these worms are not human parasites.

You can find additional information in this site on the general biology of parasitic worms and/or roundworms.

Final location of Capillaria worms

Predilection site of adult Capillaria worms depend on the species:

- Capillaria annulata = Eucoleus annulatus: mucosa of crop and esophagus

- Capillaria bursata= Aonchotheca bursata: small intestine

- Capillaria contorta = Eucoleus contortus: crop and esophagus

- Capillaria caudinflata = Aonchotheca caudinflata: small intestine

- Capillaria obsignata: small intestine

- Capillaria anatis = Capillaria retusa: cecum, occasionally the small intestine

Anatomy of Capillaria worms

Adult Capillaria worms are very thin worms (hairworms), up to 8 cm long (depending on the species) and of a whitish color. Females are longer than males. The posterior end can have flaps.

As in other roundworms, the body of these worms is covered with a cuticle, which is flexible but rather tough. The worms have a tubular digestive system with two openings, the mouth and the anus. They also have a nervous system but no excretory organs and no circulatory system, i.e. neither a heart nor blood vessels. The female ovaries are large and their opening in these worms is located just after the esophagus.

Males have a rudimentary bursa with only one spicule (with species-specific size and morphology) for attaching to the female during copulation. Females are larger than males. C. annulatus is easy to identify through the thickening of the cuticle just after the head. In C. caudinflata the female genital opening has a characteristic appendix. In C. obsignata the spicule is very long (up to 5 mm) and its sheath has transversal folds without spines.

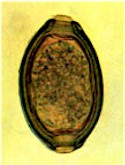

Capillaria eggs are ovoid, about ~30x70 micrometers (species-specific sizes), with a thick shell, two polar plugs, and contain a single cell (i.e. they are not embryonated when shed).

Life cycle of Capillaria worms

Some Capillaria species (e.g. Capillaria anatis, Capillaria obsignata) have a direct life cycle, i.e. there are no intermediate hosts involved. Larvae develop inside the eggs passed in the feces and become infective in 7 to 50 days, depending on species, temperature and humidity. Domestic and wild birds ingest these infective eggs with contaminated food or water. These eggs can remain infective in the environment (soil, litter, etc.) for months and can survive frost.

Other species (e.g. Capillaria annulata, Capillaria bursata, Capillaria caudinflata) have various earthworm species (e.g. Lumbricus, Eisenia, etc.) as obligate intermediate hosts. These earthworms ingest the eggs, and the eggs release the larvae inside the worms. These larvae become infective in 2 to 4 weeks. Inside the earthworms infective larvae can survive for years.

Capillaria contorta can complete development both directly and indirectly with earthworms as facultative intermediate hosts.

Once in their final hosts, infective larvae reach their predilection sites rather quickly. Larvae of some species penetrate into the gut's wall and spend part of their development there, before returning the gut's lumen where they complete development to adult worms and reproduce. Larvae of other species do not penetrate the gut's wall but complete their whole development to adults in the gut's lumen.

The prepatent periods (time between infection and first eggs shed) are species-specific:

- Capillaria annulata = Eucoleus annulatus: 2 to 4 weeks

- Capillaria bursata = Aonchotheca bursata: 3 to 4 weeks

- Capillaria contorta = Eucoleus contortus: 6 to 8 weeks

- Capillaria caudinflata = Aonchotheca caudinflata: 3 to 4 weeks

- Capillaria obsignata: 3 to 4 weeks

- Capillaria anatis = Capillaria retusa: ~4 weeks

Species with a direct life cycle are more frequent under intensive farming conditions where constant temperature and humidity are ideal for larval development in the worms' eggs shed with the feces. Species with indirect life cycles are particularly abundant in traditional farms with birds kept outdoors, especially in humid and humus-rich soils that are favorable for earthworm development. In such farms wild birds can easily introduce Capillaria and other parasitic worms from outside.

Harm caused by Capillaria worms, symptoms and diagnosis

Capillaria annulata and Capillaria contorta are the most damaging species. They can seriously harm the lining of the crop and the esophagus, especially in turkeys end pheasants, but also in chicken up to 4 months old. The lining of the crop and the esophagus becomes inflamed and swollen, which can make swallowing impossible for affected birds. Fatalities are frequent in cases of heavy infections.

The species in the intestine get into the villi and even into the intestinal glands, and in case of heavy infections they can cause enteritis and fibrosis.

Predominant clinical signs, mainly in young birds are diarrhea (mucous or even liquid), anemia, apathy, ruffled feathers, loss of appetite and weight, reduced egg production in layers, etc. Affected ducklings may not properly swim.

Diagnosis is based on detection of typical eggs in the feces and/or on identification of the worms in their predilection sites after necropsy.

Prevention and control of Capillaria infections

To prevent or at least reduce Capillaria infections it is recommended to keep the birds' bedding as dry as possible and to frequently change it, because development of the worms' eggs needs humidity. Strict hygiene of feeders and drinkers are a must to avoid or reduce their contamination with eggs. Pasture rotation is also recommended. For birds kept outdoors it is advisable to restrict their access to humid environments where earthworms are usually more abundant. All these measures are especially important for young birds, which are likely to suffer more from Capillaria infections.

Numerous classic broad spectrum anthelmintics are effective against Capillaria worms, e.g. several benzimidazoles (albendazole, fenbendazole, flubendazole, mebendazole, oxfendazole, etc.), levamisole, as well as macrocyclic lactones (e.g. ivermectin). Some compounds with a narrower spectrum are also effective against these worms, e.g. piperazine derivatives and pyrantel.

For use on poultry these active ingredients are usually available as additives for feed or drinking water, seldom as injectables or tablets (mainly for single animal treatment, typical for fighting roosters).

Most such wormers (e.g. benzimidazoles, levamisole, piperazine derivatives and pyrantel) kill the worms shortly after treatment and are quickly metabolized and/or excreted within a few hours or days. This means that they have a short residual effect, or no residual effect at all. As a consequence treated animals are cured from worms but do not remain protected against new infections. To ensure that they remain worm-free the animals have to be dewormed periodically, depending on the local epidemiological, ecological and climatic conditions.

So far no vaccine is available against Capillaria worms. To learn more about vaccines against parasites of livestock and pets click here.

Biological control of Capillaria worms (i.e. using its natural enemies) is so far not feasible.

You may be interested in an article in this site on medicinal plants against external and internal parasites.

Resistance of Capillaria worms to anthelmintics

There are a no reports on confirmed resistance of Capillaria worms to anthelmintics.

This means that if an anthelmintic fails to achieve the expected efficacy against Capillaria worms it is most likely that either the product was unsuited for the control of these worms, or it was used incorrectly.

|

Ask your veterinary doctor! If available, follow more specific national or regional recommendations for Capillaria control. |