Ixodes is a genus of hard ticks that affects wild and domestic mammals and birds worldwide: cattle, sheep, goats, horses, dogs, cats, and humans as well.

cattle, sheep, goats, horses, dogs, cats, and humans as well.

There are about 250 Ixodes species worldwide, with species-specific distribution and prevalence.

As a general rule, Ixodes ticks are less relevant for cattle and other livestock than those of the genus Amblyomma, Boophilus and Rhipicephalus in tropical and sub-tropical regions. But several species are are important dog parasites and their importance as vectors of human diseases is increasing.

The most relevant species for livestock and pests are the following:

- Ixodes holocyclus the paralysis tick of Australia; the scrub tick, etc., important for dogs and horses; Australia

- Ixodes pacificus, the Western black-legged tick; North America (West Coast)

- Ixodes persulcatus, the taiga tick, Central, North and East Europe, Siberia, North China, Japan

- Ixodes ricinus, the castor bean tick, the sheep tick, the European wood tick; important for dogs; Europe, Near and Middle East, Northern Africa

- Ixodes rubicundus, the karoo paralysis tick; Southern Africa

- Ixodes scapularis = dammini, the deer tick, the black-legged tick; important for dogs; North America, East and Gulf Coast

There are specific articleS in this site on ticks in dogs and cats, as well as on ticks in horses.

Biology and life cycle of Ixodes

As all hard ticks, Ixodes ticks are obligate parasites: they cannot survive without feeding blood of their hosts.

Ixodes ticks are medium-sized, i.e. engorged adult females are usually about 1 to max. 1.5 cm length. They have quite prominent mouthparts and are of a brownish to grayish color.

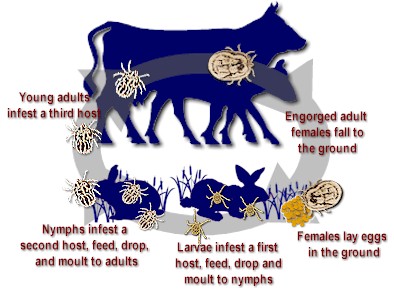

Most Ixodes ticks are three-host ticks, i.e. larvae, nymphs and adults can be found free-living in the environment waiting for a suitable host to pass by. Larvae and nymphs usually infect small mammals (e.g. rodents, rabbits, moles, but also reptiles and birds), whereas adults prefer larger ones, often dogs, but also livestock, wildlife and humans. There are other Ixodes species that infest only birds, or are quite specific of certain mammals (e.g. badgers, hedgehogs, etc.). The Ixodes life-cycle takes usually 1 to 3 years to complete, depending on the species and the climate.

All stages can survive for 10 months and much longer without feeding, and are capable of overwintering in cold regions. Due to their preferred habitats they are seldom a problem for cattle, but may affect sheep on summer grazelands. They are more frequent during the warm season, from spring to early autumn, but in cold regions can be active very quickly after an early morning frost.

Within the European species, Ixodes ricinus is certainly the most important and frequent one. It occurs in both deciduous and perennial woods, particulary along the borders to pastures and farmland, in wood clearings, along track borders, etc. Warmer south-oriented slopes are often preferred. Ixodes persulcatus occurs also deciduous, perennial and mixed forests.

Within the North American species, Ixodes scapularis is found in most of the eastern half of the USA, from the Gulf Coast up to Canada. They prefer similar habitats as Ixodes ricinus in Europe, i.e. deciduous and perennial woods, particulary along the borders to pastures and farmland, and everywhere where the white-tailed deer, its major host, is found. Ixodes scapularis is found mainly in the West Coast of the USA, from Canada down to Mexico.

Ixodes holocyclus is found all along the eastern Coats of Australia. They prevail in areas with leafy vegetation that provide humidity and shelter from direct sunlight. Ixodes rubicundus in South Africa is found on pasturelands used for sheep and goat grazing.

Click here to learn more about the general biology of ticks.

Harm and economic loss due to Ixodes

As for all ticks, Ixodes bites cause stress and blood loss to the hosts. A few ticks are usually well tolerated by livestock and pets, but infestations with dozens or hundreds of ticks can significantly weaken affected animals and cause weight loss, reduced fertility, decreased milk production, etc.

Ixodes ticks are all vectors of several tick-borne diseases of increasing importance for dogs and humans worldwide.

- Ixodes holocyclus causes tick paralysis of pets and humans. Transmits various Rickettsia diseases and the Lyme-like spirochaetal disease. Important for pets & horses in Australia, mainly in humid regions of the Eas-coast.

- Ixodes pacificus, transmits Lyme disease (borreliosis) and anaplasmosis.

- Ixodes persulcatus transmits Lyme-disease, babesiosis, and various tick-borne encephalitis.

- Ixodes ricinus, can transmit Lyme disease (borreliosis) to dogs, cattle, horses and humans; babesiosis, anaplasmosis and various viruses to livestock and pets, human encephalitis and Q fever, etc

- Ixodes rubicundus causes tick paralysis of livestock (mainly sheep and goats).

- Ixodes scapularis = dammini, transmits Lyme disease (borreliosis) as well as various anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, theileriosis of pets and humans, early summer meningoencephalitis, etc.

It seems that Ixodes ticks are expanding their range in several countries, possibly due to climate changes, but also to increased environmental protection that helps preserving or even extending their habitats. Wildlife protection and climatic changes also contribute to increase the number of potential hosts for these ticks. On the other side, more and more people visit the environments where these ticks prevail, either in recreational areas, or in peri-urban residential areas.

Ixodes ticks are usually only a minor issue for the cattle industry compared with Amblyomma and Boophilus ticks and seldom a source of economic losses. In endemic areas it can be a problem for sheep and goats on summer grazelands where these ticks prevail, e.g. in South Africa.

Non-chemical prevention and control of Ixodes on livestock

Where these ticks are a problem for cattle, a proven method to reduce such problems is to increase the amount of B. indicus "blood" in the herds. Cebu cattle (Bos indicus) and numerous indigenous breeds are naturally resistant to ticks and tick-borne diseases, whereas European breeds (Bos taurus) are not. Unfortunately, in many regions the opposite is more frequent. The reason is that producers are often urged to increase the productivity of their properties. Since they can neither reduce their costs, nor increase the cattle density of the farm, a rather cheap and easy option is to introduce more European "blood". It doesn't need significant investments or changes in the infrastructure and management of the property. Social and cultural factors also play a role: European breeds are often perceived as high-tech and prestige livestock.

Little to nothing can be done to reduce Ixodes tick populations on their natural habitats.

Pasture burning is a common practice in many regions of the world. Regarding cattle tick control, the experience is that it contributes to reduce the tick numbers to some extent, but it is certainly not enough to eliminate or substantially reduce the tick populations. But it cannot be practiced in most natural grazelands or woodlands where Ixodes ticks are a problem.

Livestock alternation doesn't help at all with Ixodes ticks, because they feed on most available livestock or wildlife. Reducing the number of wild animals can have an impact on Ixodes populations, but is usually impossible in natural grazelands.

Pasture rotation or vacation for tick reduction is not feasible with Ixodes ticks: they can survive very long without feeding and there will always be enough wild animals around to support tick populations.

Biological control of Ixodes and other ticks using their natural enemies remains a research topic has not yet delivered really effective and sustainable solutions for tick population control. Tick predators such as insects (e.g. ants, wasps), small rodents or birds (e.g. cattle egrets, guinea fowls, oxpeckers, etc.) do in fact consume significant amounts of ticks, but will not eliminate tick populations. One reason is that they are not specific tick predators, but feed on whatever is available. The most promising results have been obtained so far with so-called entomopathogenic fungi, i.e. fungi that are pathogenic for ticks and other insects (e.g. Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae, etc.). In certain countries there are commercial products for crop protection based on such fungi, and there are reports that they can effectively control ticks on livestock too. However, a systematic commercial approach to cattle or sheep tick control using such fungi is still missing. In addition, such biological control methods target tick population control and not protection of single animals or killing already attached ticks on an infected animal. For the reasons previously mentioned population control of Ixodes ticks is virtually impossible in endemic regions.

Learn more about biological control of ticks and mites.

There are no specific vaccines against Ixodes ticks. A few reports have shown efficacy of the Boophilus tick vaccine against certain other tick species, but little is know about its effect against Ixodes ticks.

There are no repellents, chemical or natural, that effectively prevent Ixodes ticks from attaching to livestock or pets, or that cause already attached ticks to detach.

There are no traps that effectively reduce Ixodes tick populations in the pastures: whatever domestic or wild animals are much more attractive for ticks than any possible trap.

So far there are no herbal remedies commercially available really effective for protecting livestock from Ixodes ticks in endemic regions.

Chemical prevention and control of Ixodes with tickicides

Chemical treatment of cattle against Ixodes ticks is often not needed in most of North America and Europe, simply because cattle seldom graze where these ticks prevail.

Sheep may need tick protection during summer grazing in regions where Ixodes ticks are endemic. In many places sheep are routinely treated once at the beginning of the outdoor grazing season, often not only for tick protection, but also against other external parasites (e.g. biting flies, blowflies).

Most products approved for tick control and prevention on livestock in these countries are based on veteran contact parasiticides of various chemical classes such as:

- Organophosphates (e.g. chlorfenvinphos, chlorpyrifos, coumaphos, diazinon, ethion, etc.)

- Amidines (mainly amitraz, also cymiazole)

- Synthetic pyrethroids (e.g. cypermethrin, deltamethrin, flumethrin, permethrin)

All are for on animal use. In most countries there are currently no tickicides approved for pasture treatment against cattle ticks. The major reason is that to effectively control the ticks on pasture the dose will be lethal for almost any invertebrate fauna in the pastures and for most of the vertebrates that feed on them (birds, reptiles, rodents, etc.). In addition, pastures would be also contaminated with chemicals, which could be toxic for livestock or leave illegal residues in meat and/or milk.

Organochlorines were vastly used in the past, but are now prohibited for livestock in most countries. Neonicotinoids are not effective against ticks. Carbamates are often not effective enough against ticks.

These veteran acaricides are mostly available as concentrates for topical administration as dips and sprays, or as ready-to-use pour-ons. As a thumb rule, dips are more effective than sprays and pour-ons, simply because sprays and pour-ons do not ensure a complete coverage of the whole body (e.g. ears, udders, perineum, below the tail etc.).

Insecticide-impregnated ear-tags, dusts and back rubbers are not suited for the control of most Ixodes ticks.

Neither macrocyclic lactones (e.g. doramectin, eprinomectin, ivermectin, moxidectin), nor tick development inhibitors (fluazuron) ensure adequate control of Ixodes ticks on livestock (or any other multi-host tick species). This means that there are no systemic tickicides suited for controlling Ixodes ticks, and consequently neither injectables, nor drenches nor feed additives.

Click here to learn more about general features of parasiticides.

Click here to learn more about delivery forms of parasiticides.

| If available, follow more specific national or regional recommendations or regulations for tick control. |

Resistance of Ixodes ticks to tickicides

There are no reports on serious resistance problems of Ixodes ticks on livestock or pets. This means that if a tickicide fails to achieve the expected efficacy, chance is almost 100% that either the product was unsuited for Ixodes control, or it was used incorrectly.

Learn more about parasite resistance and how it develops.