Spraying is a frequent alternative to plunge dipping of cattle and sheep in small to medium size properties, or for treating all kinds of livestock indoors. Spraying allows to use highly concentrated parasiticides that are diluted in water (typically 1 liter product to 500 or 1000 liters water), which results in relatively low product costs per treatment, in any case lower than those of using pour-ons or injectables.

There are three major ways of spraying livestock: Spray races, power spraying and hand spraying.

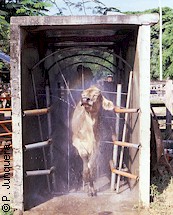

Spray races

Spray races are used in many tropical and subtropical countries to periodically treat cattle against ticks, flies and other external parasites. They are an alternative to plunge dips for medium to large properties. As a thumb rule, spray races are a good option for treating several hundred cattle. When it gets into the thousands, plunge dips are usually the better choice

There are also spray races for sheep adapted to their smaller size. They can be fix or portable and are a good option for treating several thousand sheep. In some countries shower dips are also popular, among other reasons because sheep and goats are not easily convinced to spontaneously go through a spray race.

Spray races are not used on pig or poultry.

Compared with plunge dips, spray races allow a more flexible operation, e.g. it is no problem to change the parasiticide since there is no need to dispose of the old dip wash contaminated with the parasiticide and to recharge it with fresh one, which is always bothersome and expensive for a plunge dip. Spray races are also less stressing for livestock than plunge dips, which is important for pregnant cows, calves and otherwise weaker animals.

However, as for plunge dips, the animals have to be gathered and brought to the spray race, which is always time consuming and labour intensive. In addition, a spray race needs a reliable power and water supply, which is not always granted in rural areas of less developed regions.

Running and maintaining spray races is technically more demanding than plunge dips. The nozzles have to be regularly removed and cleaned and they must be correctly adjusted to have the right pressure and ensure correct coverage, i.e. complete wetting of the hair coat. Too much pressure can result in excessive product consumption. Too low pressure will leave body parts uncovered. Dip wash must not form a mist that will not wet the hair coat properly and can be easily inhaled by tha animals. The bottom line is that it is crucial to correctly train the operators to ensure that the spray-race works properly.

It is also important that the animals spend enough time inside the spray race, i.e., that they don't run but walk through. Hanging some type of curtain (cloth or strings) may help to slow down the animals.

Dip wash filtration is crucial to avoid clogging of the nozzles with dirt carried by the animals and washed off during spraying. To reduce such dirt it is a good practice to let the animals go through a footbath before going through the spray race.

As for plunge dips a draining race is highly recommended for spray races in order to collect and recycle the dip wash that runs off the sprayed animals.

The parasiticides used in spray races are always concentrates (emulsifiable concentrates, wettable powders, wettable granules, etc.) to be diluted with water before usage. For cattle and sheep they contain mainly "veteran" parasiticides such as organophosphates, (e.g. chlorfenvinphos, chlorpyrifos, coumaphos, diazinon, ethion, etc.), synthetic pyrethroids (e.g. cypermethrin, deltamethrin, flumethrin) or amidines (mostly amitraz), alone or in various mixtures. They are used against ticks, flies, mites, lice and various cutaneous myiasis (e.g. screwworm flies). Insect development inhibitors (e.g. cyromazine) are also used on sheep, mainly against blowfly strike.

In the last years products containing spinosad have been introduced in several countries for spraying sheep (against lice and blowfly strike) as well as poultry (against poultry mites and lice). Interestingly, these spinosad products are the first really new products for spraying or dipping livestock that have been introduced since about 30 years, when the last synthetic pyrethroids were launched for this purpose.

So far, in most countries there are no products for any type of spraying containing macrocyclic lactones (e.g. ivermectin), neonicotinoids (e.g. imidacloprid) or phenylpyrazoles (e.g. fipronil).

Efficacy of spray races on cattle and sheep is usually sufficient, but not as complete as with plunge dips, because wetting of the hair coat after spraying is not as thorough as after immersion, especially in less accessible body parts such as inside the ears, the udders, beneath the tail, etc., where some tick, mite and lice species may congregate. For sheep, spraying is usually not capable of eliminating scab mites (Psoroptis ovis) and is not approved for this indication in several countries (e.g. UK).

Those products that show a stripping effect in dips (mainly organophosphates and amidines) will show it in spray races as well. The use recommendations regarding initial filling and replenishment must be carefully followed.

Quite a lot of things can go wrong with a spray race (and also with a plunge dip!). The consequence will be insufficient control and shorter protection of livestock. Occasional mistakes are not a problem and can be usually noticed and solved. Chronic unnoticed application errors are a more serious problem that can speed up development of resistance by some parasite species (e.g. cattle ticks, horn flies, blowfly strike).

Power spraying

Power spraying is used in small to medium cattle and sheep properties, but also in medium to large pig and poultry operations. Power spraying requires an initial investment in equipment, especially if a new power generator is required. However it is substantially cheaper than building a spray race or a plunge dip. However, such equipment needs regular maintenance too!

Parasiticides used for power spraying are the same as for spray races, i.e. concentrates to be diluted with water, that contain mainly organophosphates, (e.g. chlorfenvinphos, chlorpyrifos, coumaphos, diazinon, ethion, etc.), synthetic pyrethroids (e.g. cypermethrin, deltamethrin, flumethrin) or amidines (mostly amitraz), alone or in various mixtures.

In poultry operations, power spraying is often a good choice for treating large number of birds against lice, mites and other external parasites. It is also adequate for treating premises to reach cracks and other potential hiding places of several parasites, not always easy to achieve in layer houses.

Power spraying is also used in pig operations, where it also important to thoroughly wet the animals and to treat the surrounding premises as well (tubes, fencings, etc.).

Jetting is a particular variety of power spraying used for sheep in a few countries, notably in Australia. Instead of spraying the animals with a single nozzle from a certain distance, special wands with various nozzles are used to apply the liquid directly into the wool. Jetting is especially popular to protect sheep against blowfly strike.

Hand spraying with knapsack sprayers

Hand spraying, mostly using a knapsack sprayer is the cheapest way of applying parasiticides to all kinds of livestock. It is also the most popular for millions of small farmers in less developed countries that have to treat a few dozen cattle or a few hundred sheep, goats or birds. The only investment is the knapsack sprayer and personal work.

Most products available for plunge dipping, spray races and power spraying are available for hand spraying as well, just in small packs of 10 to 50 ml, enough to fill one or two knapsack sprayers. They are concentrates to be diluted with water that contain mainly organophosphates, (e.g. chlorfenvinphos, chlorpyrifos, coumaphos, diazinon, ethion, etc.), synthetic pyrethroids (e.g. cypermethrin, deltamethrin, flumethrin) or amidines (mostly amitraz), alone or in various mixtures.

The major disadvantage of hand spraying is that it is seldom done correctly and efficacy is often poor. Each animal must be treated thoroughly until it is completely wet, including the udders, the belly, below the tail, etc. Theoretically 2 to 5 liters (depending on the animals size and the hair coat) of spray wash are needed for each sheep or cattle (as much as they would get in a plunge dip!) and 1 liter for each pig. This requires discipline and considerable effort.

Instead, it is quite frequent to spray altogether a group of animals in an enclosure or along a race, where they get a bit of liquid on the back and perhaps on the flanks and the head. Even if a worker wants to do it right, he often gets tired before all the animals have been treated: the last ones won't be as thoroughly treated as the first ones. This way or working can provide some relief against certain parasites, but is certainly inadequate to reduce the parasite population. And it often means under dosing, which favors the development of resistance by several parasites.