Amblyomma is a genus of hard ticks  that is found mainly in topical and subtropical regions of Africa and Amercia.

that is found mainly in topical and subtropical regions of Africa and Amercia.

Amblyomma ticks affect all kinds of domestic and wild animals including cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses, dogs and cats, as well as birds, reptiles, etc. Humans are affected as well.

There are more than 100 species worldwide.

The most relevant species for livestock, dogs and cats are:

- Amblyomma americanum, the lone star tick; important for dogs in North America; parts of North America

- Amblyomma cajennense, the Cajenne tick; important for livestock and dogs; Americas, tropical and subtropical

- Amblyomma hebraeum, the bont tick, the Southern Africa bont tick; important for livestock; Africa, South of the equator

- Amblyomma maculatum, the Gulf Coast tick; North and South America

- Amblyomma variegatum, the tropical bont tick; important for livestock; parts of Africa, Caribbean (introduced from Africa in the 19th century).

In 2014 it has been reported that Amblyomma cajennense, which until now was considered as a single species includes in fact 6 independient species: Amblyomma cajennense strict sense (mainly in the Amazone region), Amblyomma patinoi (in the Eastern cordillera of Colombia), Amblyomma interandinum (in the interandean valley of Peru), Amblyomma mixtum (from Texas down to Ecuador), Amblyomma tonelliae (mainly in the dry Chaco from Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia), and Amblyomma sculptum (in humid regions of Northern Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay en certain Brazilian states).

There are no Amblyomma ticks of major veterinary importance in Europe.

Regional prevalence and distribution strongly depends on climatic and ecologic conditions.

In the regions where they prevail, all these tick species are highly relevant for cattle, locally also for horses, sheep and goats. Pigs and poultry kept outdoors can also be affected. All species can attack dogs as well, especially in rural environments and in peri-urban residential or recreational areas with abundant wildlife. Cats can be also affected, but usually much less than dogs.

There are specific articles in this site on ticks in dogs and cats, as well as on ticks in horses.

Biology and life cycle of Amblyomma ticks

Amblyomma ticks are quite big, engorged adult females can reach >2.5 cm length, larger than a hazelnut. They have prominent mouthparts (capitulum) and the dorsal shield (scutum) often shows colored patterns typical for each species. As all ticks, those of the genus Amblyomma are also obligate parasites: they cannot survive without sucking blood from their hosts.

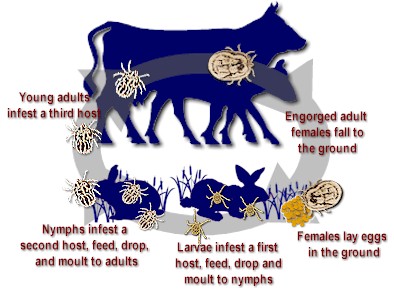

Most Amblyomma ticks are three-host ticks. This means that larvae, nymphs and adults detach from the host and drop to the ground after each blood meal. After molting in the ground, larvae and nymphs have to wait for a new host for the next blood meal, whereas adult females lay their eggs ion the ground and die. Therefore duration of the life cycle strongly depends on how long larvae and nymphs have to wait for finding a new host. Amblyomma americanum can complete its life cycle in about 4 months, whereas Amblyomma cajennense and Amblyomma americanum usually need about 12 months. These ticks can live for 2 to 4 years.

The number of eggs an adult female can deposit ranges from about 5'000 for Amblyomma cajennense, to 20'000 for Amblyomma hebraeum. Free living questing stages (i.e. larvae, nymphs and hungry adults) can survive up to one year without feeding waiting for a suitable host to pass by, although this strongly depends on the weather conditions: by hot and humid weather survival is shorter. Normally there is only one generation a year for most species.

Amblyomma ticks prefer rangelands (shrublands, woodlands, savannas, etc.) with abundant bushes and small trees that provide shelter from direct sun exposure, and rich in wildlife (small and large mammals, birds, etc,) as primary hosts. Amblyomma cajennense and Amblyomma maculatum prefer humid and hot climates, often close to coastlines. Amblyomma hebraeum prefers warm and moderately humid savannas in Africa South of the Equator. Amblyomma variegatum tolerates both dry environments and tropical forests.

Usually all developmental stages (i.e. larvae, nymphs and adults) are found free in the environment during the whole year. This means that livestock and pets can become infested by any stage any time of the year. However, under local climatic conditions a seasonal distribution is often observed. This is the case for Amblyomma cajennense in the Golf of Mexico, where larvae predominate from February to May, nymphs from June to August, and adults from October to December.

Each species has its preferences regarding preferred hosts and preferential sites for attachment. As a general rule, larvae and nymphs will prefer small animals (rodents, birds, reptiles), whereas adult ticks will prefer larger mammals. Amblyomma americanum and Amblyomma hebraeum attach preferably to body parts with less hair (e.g. axillae, perineum, under the tail); Amblyomma cajennense prefers the belly and other lower body parts; Amblyomma maculatum is often found in the ears. Amblyomma variegatum prefers the underbelly, the dewlap, genitalia, around the anus, etc. However tick attachment preferences can vary strongly on different hosts.

Click here to learn more about the general biology of ticks.

Harm and economic loss due to Amblyomma ticks

As for all ticks, Amblyomma bites cause stress and blood loss to the hosts. A few ticks are usually well tolerated by livestock and pets, but infestations with dozens or hundreds of ticks can significantly weaken affected animals and cause weight loss, reduced fertility, decreased milk production, etc.

Severe infestations may be fatal for weak or otherwise sick animals. Such severe infestations are not uncommon in rural areas of tropical and subtropical regions with abundant wildlife. The strong mouthparts of Amblyomma ticks cause quite deep injuries that often attract screwworms or other myiasis flies.

In addition, Amblyomma ticks transmit a number of livestock and pet diseases.

- Amblyomma hebraeum and Amblyomma variegatum are vectors of Ehrlichia (=Cowdria) ruminantium, a blood parasite that causes heartwater, a highly dangerous disease of ruminants.

- Amblyomma hebraeum transmits also Rickettsia africae, the agent of African tick-bite fever of cattle, humans, and wildlife.

- Amblyomma cajennense is a vector of Rickettsia rickettsii that causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever, which can be a serious disease for humans.

Non-chemical prevention and control

Several measures to prevent infestation of cattle and other livestock with Amblyomma ticks are basically the same as those described for Boophilus ticks.

Cebu cattle (Bos indicus) and numerous indigenous breeds are naturally resistant to ticks and tick-borne diseases, whereas European breeds (Bos taurus) are not. An obvious and proven method to reduce cattle tick problems in tick endemic regions is to increase the amount of B. indicus "blood" in the herds. This has been done successfully in a few regions.

Unfortunately, in many other regions the opposite is more frequent. The reason is that producers are often urged to increase the productivity of their properties. Since they can neither reduce their costs, nor increase the cattle density of the farm, a rather cheap and easy option is to introduce more European "blood". It doesn't need significant investments or changes in the infrastructure and management of the property. Social and cultural factors also play a role: European breeds are often perceived as high-tech and prestige livestock.

Pasture burning is a common practice in many regions of the world. Regarding cattle tick control, the experience is that it contributes to reduce the tick numbers to some extent, but it is certainly not enough to eliminate or substantially reduce the tick populations.

Pasture plowing contributes to reduce potential shelters for ticks below the vegetation and increases their exposure to direct sunlight, which shortens their survival off the hosts. But plowing is never enough to eliminate tick populations, and most properties where Amblyomma ticks are a problem are not suitable for regular plowing the pastures.

Converting bushland, shrubland and woodland to pure grassland can reduce the number of Amblyomma ticks, because they need shelter from direct sunlight for survival, especially by hot and humid weather. But this can favor Boophilus ticks and is often unwanted or not feasible for ecological or economic reasons (can be very expensive...).

Livestock alternation doesn't help at all with Amblyomma ticks, because they feed on whatever livestock or wildlife is available. Reducing the number of wild animals can have an impact on Amblyomma populations, but is often impossible (e.g. in vast parts of Africa) or simply unwanted.

Pasture rotation or vacation is not feasible with Amblyomma ticks: they can survive for years without feeding and there will always be enough wild animals around to support tick populations.

Biological control of Amblyomma and other ticks using their natural enemies remains a research topic has not yet delivered really effective and sustainable solutions for tick population control. Tick predators such as insects (e.g. ants, wasps), small rodents or birds (e.g. cattle egrets, guinea fowls, oxpeckers, etc.) do in fact consume significant amounts of ticks, but will not eliminate tick populations. One reason is that they are not specific tick predators, but feed on whatever is available. The most promising results have been obtained so far with so called entomopathogenic fungi, i.e. fungi that are pathogenic for ticks and other insects (e.g. Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae, etc.). In certain countries there are commercial products for crop protection based on such fungi, and there are reports that they can effectively control ticks on cattle too. However, a systematic commercial approach to cattle tick control using such fungi is still missing. In addition, such biological control methods target tick population control and not protection of single animals or killing already attached ticks on an infected animal. For the reasons previously mentioned population control of most Amblyomma ticks is virtually impossible in endemic regions.

Learn more about biological control of ticks and mites.

A few reports have shown a certain effect of the recombinant Boophilus tick vaccine on Amblyomma populations, approved only for use on cattle. However, for the time being it is certainly not a viable solution for most situations where Amblyomma ticks are a problem.

There are no repellents, chemical or natural that effectively prevent Amblyomma ticks from attaching to livestock, or that cause already attached ticks to detach.

There are no traps that effectively reduce tick populations in the pastures: whatever domestic or wild animals are much more attractive for ticks than any possible trap.

So far there are no herbal remedies commercially available really effective for protecting livestock from Amblyomma ticks in endemic regions.

Chemical prevention and control

Chemical control and prevention of Amblyomma ticks on livestock is based on the same parasiticides used for the control of Boophilus cattle ticks.

However, there is a substantial difference between Boophilus ticks and Amblyomma ticks. For Boophilus ticks, only the very small larvae wait for hosts in the environment. Once they infect cattle they remain on the same host for about three weeks until development is completed and engorged adult females drop to the ground. There are neither hungry nymphs nor hungry adult Boophilus ticks in the environment waiting for hosts to pass by. During the first two weeks after infestation with larvae the infected animals "seem" tick free and the infestation becomes "visible" only later, when the adult females (developed from the hungry larvae) start to feed and engorge. Since most farmers treat their herds when they "see" ticks, retreating every 3 or more weeks will keep the herds free of "visible" ticks long enough for the farmer to feel comfortable (see also the article on Boophilus ticks for additional information).

In contrast with this, Amblyomma ticks infest livestock at all developmental stages and are also larger. This means that hungry larvae, nymphs and adults wait in the environment for hosts to pass by. A few days after an animal has been infested it will carry smaller or larger "visible ticks" (engorged larvae, nymphs or adults). If it is treated with a tickicide, the ticks on the animal will be killed. But, pretty soon, it will pick new ones and usually 5 to 10 days after the last treatment it will carry "visible ticks" again. The bottom line is that infestations with Amblyomma (and other three-host) ticks usually require more frequent chemical treatments than infestations with Boophilus ticks. In numerous African regions heartwater prevention requires treating cattle almost weekly during most of the year.

Another consequence of the behavior of Amblyomma ticks is that they are significantly tougher to kill with chemicals than Boophilus ticks. They usually require a higher dose of the chemical, even in the laboratory. And they remain on the hosts much shorter than Boophilus ticks. Whereas Boophilus ticks on treated cattle remain exposed to the tickicide for up to 3 weeks, Amblyomma ticks will remain on a host only for a few days (depending on species and developmental stage), the time to take a blood meal and drop off.

For all these reasons, there are fewer parasiticides appropriate for controlling Amblyomma ticks than for Boophilus ticks.

Basically only veteran contact parasiticides of various chemical classes are appropriate for the control of Amblyomma ticks on livestock:

- Organophosphates (e.g. chlorfenvinphos, chlorpyrifos, coumaphos, diazinon, ethion, etc.)

- Amidines (mainly amitraz, also cymiazole)

- Synthetic pyrethroids (e.g. cypermethrin, deltamethrin, flumethrin, permethrin)

All are for on animal use. In most countries there are currently no tickicides approved for pasture treatment against cattle ticks. The major reason is that to effectively control the ticks on pasture the dose will be lethal for almost any invertebrate fauna in the pastures and for most of the vertebrates that feed on them (birds, reptiles, rodents, etc.). In addition, pastures would be also contaminated with chemicals, which could be toxic for livestock or leave illegal residues in meat and/or milk.

Most of these products are also effective against other parasites as well (e.g. horn flies, stable flies, mites, lice, etc.), including other tick species (e.g. Boophilus spp, Rhipicephalus spp). Amidines are a notable exception: they do not control parasitic flies. Mixtures are also quite frequent (e.g. organophosphate + synthetic pyrethroid, amidine + synthetic pyrethroid, etc.) mostly to broaden the spectrum of activity or as an attempt to overcome Boophilus resistance to one of the active ingredients.

Where Amblyomma ticks are a problem for cattle, Boophilus ticks are usually a problem too, i.e., both species need to be controlled simultaneously. It can be a tough business if Boophilus has developed resistance to one or more of these veteran tickicides.

Organochlorines were vastly used in the past, but are now prohibited for livestock in most countries. Neonicotinoids are not effective against ticks. Carbamates are often not effective enough against ticks.

These classic tickicides are mostly available as concentrates for topical administration as dips and sprays, or as ready-to-use pour-ons. Most such products are approved for use on dairy cows: withholding periods depend on each product and national regulations.

As a thumb rule, dips are more effective than sprays and pour-ons, simply because sprays and pour-ons do not ensure a complete coverage of the whole body (e.g. ears, udders, perineum, below the tail etc.).

Insecticide-impregnated ear-tags, dusts and back rubbers are not suited for the control of the major Amblyomma species.

For the reasons previously explained (different life-cycle, shorter exposure to chemicals on treated animals, etc.), neither macrocyclic lactones (e.g. doramectin, eprinomectin, ivermectin, moxidectin), nor tick development inhibitors (fluazuron) ensure adequate control of Amblyomma ticks (or any other multi-host tick species). This means that there are no systemic tickicides suited for controlling Amblyomma ticks, and consequently neither injectables, nor drenches nor feed additives.

Residual effect and treatment regimes

Residual effect of most contact tickicides against Amblyomma ticks is not longer than 7 days. This means that for keeping livestock reasonably free of ticks weekly treatments are often required, especially during the high tick season in heartwater endemic areas.

In regions where Amblyomma ticks show a seasonal pattern, strategic treatments at the beginning of the season are highly recommended, even if the herds don't carry "visible ticks". It is crucial to hit the first generation of larvae in order to prevent the build-up of large tick populations in the fields later in the season. However, if wildlife is abundant (e.g. in Africa) Amblyomma larvae may find enough alternative hosts.

Eradication of Amblyomma ticks (and other multi-host ticks) can be considered as virtually impossible due to their capacity for feeding on almost any wild mammals or birds, which cannot be treated with tickicides. A special case is the eradication of Amblyomma variegatum in the Caribbean, a campaign run by several international organizations between 1994 and 2008 with variable success. The reason for trying it against most odds is that the risk that Amblyomma variagatum invades mainland America is real (transported by birds). And the ticks would introduce Ehrlichia (=Cowdria) ruminantium, the causative agent of heartwater, with could be a disaster for the American livestock industry.

A particularly complicated situation can develop in regions where both Amblyomma (and/or other multi-host ticks) and Boophilus ticks are endemic (e.g. in many regions in Africa and tropical Latin America). The reason is that most tickicides will work against Amblyomma ticks, but some will not work against Boophilus ticks because they have developed resistance. This may require treating cattle with one tickicide against Amblyomma, and with another one against Boophilus ticks.

Where these ticks are a problem for sheep, they can usually be controlled with the same products approved for cattle.

Click here to learn more about general features of parasiticides.

Click here to learn more about delivery forms of parasiticides.

| If available, follow more specific national or regional recommendations or regulations for tick control. |

Resistance of Amblyomma to tickicides

There are a few reports on field resistance of Amblyomma ticks against organophosphates, synthetic pyrethroids and amitraz. But so far this is not a widespread problem, nothing comparable with the resistance problems of Boophilus ticks. For most properties affected by Amblyomma ticks it can be assumed that resistance is not an issue. Therefore, if a product fails to achieve the expected efficacy, chances are high that either the product was unsuited for Amblyomma control, or it was used incorrectly.

Learn more about parasite resistance and how it develops.