Lice are small insects (1 to 5 mm) without wings. Most species suck blood and belong to the order Phtiraptera. They are found worldwide, without a preference for particular climatic regions.

Incidence seems to be higher than perceived by the farmers. In the UK analysis of hides in abattoirs resulted in more than 80% showing some degree of lice damage.

Most lice species affecting livestock are species specific, and consequently there is no risk of transmission from one species to the other (e.g. from sheep to cattle, from dogs to cats or humans, etc.).

Infestations of animals with lice are medically called pediculosis.

Biology and life cycle of lice on cattle

Lice undergo an incomplete metamophosis. The life cycle takes about 1 month to complete. Each female deposits 20 to 50 eggs (nits) during her lifetime. She deposits them one by one to single hairs. Incubation lasts 4 to 20 days. Young nymphs look like adults but are smaller. Adult life lasts 2 to 6 weeks. Off the host most lice survive only for a few days.

Lice spend their whole life on the same hosts: transmission from one host to another one is by contact. Transmission from herd to herd is usually through introduction of an infested animal, but flies may also occasionally transport lice.

Chewing lice feed on skin and hair debris as well as on skin secretions. The other species have mouthparts adapted for piercing the skin and suck blood.

Lice infestations develop mostly in the colder season and peak in late winter and early spring. Usually they decline during the hotter season. Stabling the animals during the winter season favors overcrowding, which makes contact transmission easier. And the usually poorer diet during winter weakens their natural defenses of cattle against lice infestations. The denser and more humid hair coat in winter offers an excellent environment for lice development as well.

In spring, food improves quickly when the herds start grazing fresh pastures. The shorter hair and the exposure to the sun reduce skin humidity, and free grazing ends overcrowding in the winter quarters, which also diminishes transmission. As a consequence lice infestation usually recede spontaneously during the summer season. However, a few lice usually manage to survive in some animals that will re-infest the whole herd when it comes back to the winter quarters for the next winter.

Click here to learn more about the general biology of insects.

Main species of lice on cattle

Most parasitic lice of cattle are blood-sucking, and belong to the group called Anoplura, whereas one species does not suck blood, but is a chewing lice belonging to the group of Mallophaga. However, most cattle herds have mixed infestations caused by several lice species.

Most parasitic lice of cattle are blood-sucking, and belong to the group called Anoplura, whereas one species does not suck blood, but is a chewing lice belonging to the group of Mallophaga. However, most cattle herds have mixed infestations caused by several lice species.

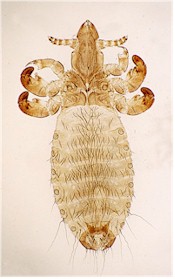

Bovicola bovis (= Damalinia bovis), the biting louse of cattle, is a chewing louse. It is very small (1 to 2 mm long) and occurs worldwide but is more frequent in regions with cold winters. It is one of the most damaging louse species on cattle. It is mostly found on the rump, shoulders, neck and head of cattle, but its preferential sites may change along the season.

Haematopinus eurysternus, the short-nosed cattle lice, is the largest among cattle lice (3 to 5 mm long). It is a bloodsucking louse that infests cattle all around the world. It is mostly found on the head, especially around the horns, the eyes and the ears, but also on the neck, the shoulders and the base of the tail. Some authors consider it as the most damaging louse for cattle.

Haematopinus quadripertusus, the tail switch louse, is another bloodsucking louse, quite large (3 to 4 mm long), found mostly in America, Asia, Australia and Sub-Saharian Africa. Originally it infested Cebu cattle (Bos indicus) but it will also infest crossbred cattle. This louse can survive up to 40 days off the host, although most individuals will die in a few days.

Solenopotes capillatus, the small blue sucking louse, is the smallest among the bloodsucking lice of cattle (1 to 2 mm long), and is found worldwide too. It usually feeds on the head, neck, shoulders, back and tail of cattle, often clustered in large numbers.

Linognathus vituli, the long-nosed sucking louse, is the most common blood sucking louse of cattle (about 2.5 mm long) and occurs worldwide. It can be found all over the body, but prefers feeding on the head, shoulders, rump and back of cattle.

Damage, harm and economic importance

Damage of lice to cattle can be considerable. Bites from bloodsucking and chewing lice are rather irritating and affected animals react through licking and vigorous rubbing. This can result in hair loss and skin injuries that can be infected with secondary bacteria. Such stress can reduce weight gains and milk production for up to 10% and makes the animals more susceptible for other diseases.

Low to moderate infestation is probably not very detrimental to most cattle and studies on the effect of lice control on weight gains in cattle are not conclusive. Young animals seem to be more susceptible to suffer from severe lice infestations.

Heavy infestations can also affect hide and leather quality.

Cattle lice are not vectors of other cattle diseases.

Prevention and control

Prevention

The best way to prevent lice infestations is to avoid overcrowding, especially during confinement in winter, and to keep the animals well fed and in good health conditions. Whatever weakens the animals makes them more susceptible for louse infestations.

In regions with cold winters (e.g. most of Europe, North America and Canada, Southern Argentina, etc.) lice can become a serious winter pest, especially damaging for dairy cattle. For herds at risk a preventative treatment at late fall or early winter is highly recommended and, depending on the product used, it can also serve to prevent mange, which is a winter pest as well. If an outbreak happens in confined animals, transmission among animals is very fast. To avoid it it is essential to treat all the animals in the herd, and not only those that already show clinical symptoms. Many already infested animals may not yet show symptoms and the infection will progress if left untreated.

To avoid introducing lice in clean herds, all incoming animals must be preventatively treated.

In warmer regions without a marked cold season (e.g., in tropical and sub-tropical areas), herds usually remain outdoors all the year through. This is often enough to avoid severe lice outbreaks, since transmission among animals is strongly reduced in absence of overcrowding. In addition, in such regions it is quite common to periodically treat the herds with parasiticides for fly and tick control. Many pour-ons, dips and sprays that control flies or ticks are also effective against lice. All these factors contribute to make louse infestations less of a problem in warm regions.

Control

Classical concentrates for dipping and spraying with traditional contact insecticides (mainly organophosphates, synthetic pyrethroids and amidines) are quite effective lousicides for cattle. However, such insecticides do not kill lice eggs (nits) and their residual effect is usually not long enough to ensure that immature lice are killed when hatching out of the eggs. Therefore it is highly recommended to repeat the lousicide treatment 2 to 3 weeks later.

Numerous ready-to-use pour-ons (backliners) are also available for lice control on cattle. Several ones contain similar active ingredients as dips and sprays, often in mixtures (typically organophosphate + pyrethroid). Besides, there are several pour-ons containing systemic macrocyclic lactones (e.g. ivermectin, moxidectin, etc.) that are also effective against a number of other internal as well as external parasites (e.g. gastrointestinal nematodes, various myiasis, horn flies, etc). Those pour-ons with eprinomectin are also allowed for use on dairy cattle.

Injectable macrocyclic lactones will also control biting (i.e. blood-sucking) lice, since they reach the parasites through the blood stream of the host. But control of chewing lice (that do not suck blood) is usually incomplete.

Warning: Use of macrocyclic lactones against lice in regions where warble flies (Hypoderma spp.) occur may cause an adverse reaction in the host if is infected with migrating Hypoderma larvae. Such larvae will be killed as well by the endectocides and this may cause a serious allergic reaction in the host.

A few insecticide impregnated ear-tags indicated for the control of horn flies may reduce lice infestations as well but do not provide complete control.

Self-treatment devices such as dusts and back rubbers, mostly with organophosphates, can be effective against lice, but have bee widely substituted by more efficient and convenient products.

Research on the use of entomopathogenic fungi (Metarhizium anisopliae) for the biological control of lice has shown promising results. However, there are still no such commercial products in the market. Learn more about biological control of insects.

For the time being there are no vaccines that will protect cattle by making them immune to lice. There are no repellents, natural or synthetic that will keep lice away from cattle. And there are no traps for catching cattle lice, for the simple reason that they spend their whole life on the animals and therefore there are no stages in the environment searching or waiting for a host.

Click here if you are interested in medicinal plants for controlling lice and other external parasites of livestock and pets.

There is also additional information in this site on the general features of parasiticides and ectoparasiticides, as well as on parasiticidal chemical classes and active ingredients.

| If available, follow more specific national or regional recommendations or regulations for cattle lice control. |

Insecticide resistance of lice on cattle

So far there are almost no reports on confirmed resistance of cattle lice to lousicides.

This means that if a particular product has not achieved the expected control, it is most likely because the product is not adequate or it was not used correctly, not because lice have become resistant.

Learn more about parasite resistance and how it develops.