Crenosoma vulpis, the fox lungworm is a parasitic roundworm that has dogs, occasionally cats and numerous wild carnivores (e.g. foxes, wolves, badgers, hedgehogs, raccoons) as final hosts.

that has dogs, occasionally cats and numerous wild carnivores (e.g. foxes, wolves, badgers, hedgehogs, raccoons) as final hosts.

It is found in Europe, North America and Asia, with a variable incidence depending on the particular region. In endemic regions more than 50% of foxes can be infected. Different studies showed that about 1% of the dogs were infected in Germany, and about 3% in Canada.

The disease caused by Crenosoma vulpis is called crenosomiasis.

Crenosoma vulpis does not infect livestock (cattle, sheep, goats, swine, etc.), horses or poultry.

Are dogs or cats infected with Crenosoma vulpis contagious for humans?

- NO. The reason is that this worm is not a human parasite.

You can find additional information in this site on the general biology of parasitic worms and/or roundworms.

Final location of Crenosoma vulpis

Predilection sites of adult Crenosoma vulpis are the bronchi and bronchioles, often the trachea as well.

Anatomy of Crenosoma vulpis

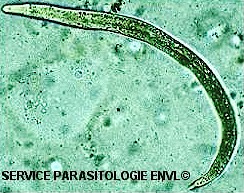

Adult Crenosoma vulpis are rather small worms, usually not more than 16 mm long and 1 mm thick, with a dark brownish color. Males are shorter than females.

As in other roundworms, the body of Crenosoma vulpis is covered with a cuticle, which is flexible but rather tough. Specific for these worms are ring-shaped cuticular folds covered with small spines that look somehow like a horsetail plant (Equisetum). The worms have a tubular digestive system with two openings.

They also have a nervous system but no excretory organs and no circulatory system, i.e. neither a heart nor blood vessels. Males have chitinous spicules for attaching to the female during copulation.

The eggs hatch already in the host's airways and consequently the feces of the host do not contain eggs but young larvae.

Life cycle and biology of Crenosoma vulpis

Crenosoma vulpis has an indirect life cycle, with dogs, occasionally cats and numerous wild carnivores as final hosts, and snails or slugs as intermediate hosts. In contrast with other lungworms (e.g. Aelurostrongylus) it seems that transport (paratenic) hosts are not involved in the life cycle of Crenosoma vulpis.

Adult female worms lay eggs in the lungs of infected cats. Young larvae hatch out of the eggs already in the airways and start migrating towards the mouth. Coughing, sneezing or the mucus brings them to the mouth, where they are swallowed. Subsequently these larvae are shed with the host's feces. These larvae are capable of actively penetrating into snails or slugs.

Inside these intermediate hosts they develop to L3 larvae in 2 to 3 weeks. When dogs, foxes or other suitable final hosts eat infected snails or slugs, the infective larvae are released in their stomach, penetrate the gut's wall and migrate towards the lungs along the blood vessels. They settle down in bronchi and bronchioles. There they complete development to adult worms and reproduce.

The time between infection and first larvae found in the feces (prepatent period) is about 20 days.

Harm caused by Crenosoma vulpis, symptoms and diagnosis

Infections with a few worms are usually benign, cause no clinical signs and recede spontaneously. Massive infections cause no specific symptoms such as chronic cough, sneezing, nasal discharge, retching, weakness, loss of appetite, inflammation of the trachea or the bronchi, etc.

Symptoms often resemble those of allergic bronchitis. Very severe cases can cause bronchial pneumonia. Fatalities are very seldom, only in cases of massive sudden infection of the lungs with larvae.

Diagnosis is confirmed through detection of larvae (Baermann method) in the feces. However, shedding of larvae is intermittent, i.e. false negatives are possible. Examination of bronchial liquid or tracheal wash for larvae is more reliable.

Prevention and control of Crenosoma vulpis

In endemic regions dogs should be prevented from eating slugs or snails that act as intermediate hosts. But this may be rather difficult to achieve in rural regions where the dogs are often outdoors.

Some anthelmintic active ingredients (e.g. febantel, fenbendazole, ivermectin, levamisole, milbemycin oxime) are known to be effective against Crenosoma vulpis infections. However, since most commercial dewormers are not approved for use against this worm, the veterinary doctor has to determine a special treatment regime.

There are so far no true vaccines against Crenosoma vulpis. To learn more about vaccines against parasites of livestock and pets clic k here.

Biological control of Crenosoma vulpis (i.e. using its natural enemies) is so far not feasible.

You may be interested in an article in this site on medicinal plants against external and internal parasites.

Resistance of Crenosoma vulpis to anthelmintics

So far there are no reports on resistance of Crenosoma vulpis to anthelmintics.

This means that if an anthelmintic fails to achieve the expected efficacy, chance is very high that either the product was unsuited for the control of Crenosoma vulpis, or it was used incorrectly.

|

Ask your veterinary doctor! If available, follow more specific national or regional recommendations for Crenosoma vulpiscontrol. |