Mesocestoides is a genus of parasitic flatworms that has dogs, cats and some wild canids (e.g. foxes, coyotes, wolves, etc.) as final hosts. Some species affect also birds, and very seldom humans.

The most relevant species for dogs and cats are:

- Mesocestoides lineatus and Mesocestoides litteratus, found in Europe, Africa and Asia.

- Mesocestoides vogae (= Mesocestoides corti) and Mesocestoides variabilis, found in America.

Incidence depends on the species and the region. In some European countries more than 70% of the fox population can be infected. As a general rule it is not very frequent in dogs and cats.

The disease caused by Mesocestoides tapeworms is called mesocestoidosis or mesocestoidiasis.

Mesocestoides does not affect cattle, sheep, goats, swine or horses.

Are dogs or cats infected with Mesocestoides tapeworms contagious for humans?

- NO. Not directly through contact with the infected pet or its feces. BUT: humans can be infected after ingesting first intermediate hosts (insects, mites) or after eating uncooked snakes, lizards, frogs, or other intermediate hosts containing infective tetrathyridia. Human infections are extremely unsual in developed countries. For additional information read the chapter on the life cycle below.

You can find additional information in this site on the general biology of parasitic worms and/or tapeworms.

Final location of Mesocestoides

Predilection site of adult Mesocestoides tapeworms is the small intestine.

Anatomy of Mesocestoides

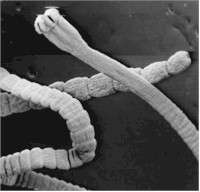

Adult Mesocestoides have the typical ribbon-like shape and structure of most tapeworms. They have a whitish color and can be up to 150 cm long and 2-3 mm wide. Gravid segments have a characteristic structure called the parauterine organ that contains masses of eggs.

The head (called scolex) has 4 suckers but no hooks. The main body (called strobila) has up to 500 segments (called proglottids). Gravid segments that are shed with the host's feces are longer than broad. Otherwise, as other tapeworms, Mesocestoides has neither a digestive tube, nor circulatory or respiratory systems. It doesn't need them because each proglottid absorbs what it needs directly through its tegument.

Each proglottid has its own, reproductive organs of both sexes (i.e. they are hermaphroditic) and excretory cells known as flame cells (protonephridia). The reproductive organs in each proglottid have a common opening called the genital pore. In young proglottids all these organs are still rudimentary. They develop progressively, which increases the size of the proglottid as it moves towards the tail.

Mature gravid proglottids are full of eggs and detach from the strobila (i.e. the chain of segments) to be shed outside the host with its feces. Shed segments are motile.

The eggs have an oval to almost spherical form and are quite small (~40 to 50 micrometers). Each egg contains an already developed larva (oncosphere or hexacanth). As many other tapeworms, Mesocestoides can produce millions of eggs during its lifetime.

Life cycle and biologyof Mesocestoides

Mesocestoides tapeworms have an unusual three-host indirect life cycle with cats, dogs and other wild carnivores as final hosts, and two intermediate hosts (most tapeworm species have only one):

- The first intermediate hosts are supposed to be arthropods such as ants, beetles, oribatid mites, etc. but so far no particular species has been shown to really act as first intermediate host in nature.

- The second intermediate hosts are small vertebrates: reptiles, amphibians, birds and small mammals.

The eggs of adult worms in the intestine of the final host are shed with its feces still inside the gravid segments full of eggs. Once outside the gravid segments release the eggs, which are supposed to be ingested by arthropods. The eggs hatch in the intestine of these intermediate hosts and the young tapeworm larvae penetrate into their body cavity (hemocoel), where they develop to cysticercoids.

Small vertebrates (snakes, lizards, frogs, birds, rats, mice, etc.) ingest the infected arthropods and the cysticercoids are released in their gut. They migrate through the gut's wall and into various organs (mainly the lungs and the liver) and develop further to an infective larval stage, in this particular case called tetrathyridium. In several species these infective larvae can reproduce asexually.

The final hosts (cats, dogs, etc.) ingest the small vertebrates infected with tetrathyridia. After digestion the young tapeworms are released, attach to the gut's wall and start producing segments.

The prepatent period (time between infection of the final hosts and first eggs shed with the feces) is 2 to 3 weeks.

It can also happen that final hosts ingest a first host infected with cysticercoids. In this case, the cysticercoids will behave as in the second intermediate host, i.e. they will migrate through the gut's wall and develop to tetrathyridia in the abdominal cavity and several organs.

Harm caused by Mesocestoides, symptoms and diagnosis

Intestinal infections of dogs or cats with adult Mesocestoides worms are usually benign and without clinical signs. Loss of appetite, diarrrhea and mucous feces has been occasionally described. Infection of internal organs with tetrathyridia can also lead to loss of appetite, fluid accumulation in the peritoneal cavity (ascites), peritonitis, tissue damage and appearance of granulomas when the immune system of the host tries to isolate the tetrathyridia. However, these clinical signs are not specific and can be due to other disturbances.

Diagnosis is usually done through detection of gravid segments in the feces of infected animals. They often have a barrel-like shape and contain the characteristic parauterine organ absent in other tapeworm species of dogs and cats.

Prevention and control of Mesocestoides spp

There are no really effective preventative measures that prevent cats and dogs to become infected with Mesocestoides tapeworms. Urban pets are usually much less at risk of becoming infected. Pets in rural environments are more at risk due to hunting or scavenging on small vertebrates infected with tetrathyridia.

Effective prevention and control can be achieved with numerous anthelmintic products. Some products contain active ingredients with broad-spectrum anthelmintic efficacy such as benzimidazoles (e.g. fenbendazole, febantel, mebendazole), other contain specific taenicides such as praziquantel and epsiprantel, the latter often in combination with nematicides (e.g. levamisole, milbemycin oxime, pyrantel, etc.) to cover a broader spectrum of worms.

Most of these pet wormers are available in formulations for oral delivery either as solids (tablets, pills, etc.) or as liquids (drenches, suspensions, etc.). There are also a few injectable and spot-on (= squeeze-on = pipettes) taenicides in some countries (mainly with praziquantel).

Most wormers kill the worms shortly after treatment and are metabolized and/or excreted within a few hours or days. This means that they have a short residual effect, or no residual effect at all. As a consequence treated animals are cured from worms but do not remain protected against new infections. To ensure that they remain worm-free the pets have to be dewormed periodically, depending on age and the local epidemiological, ecological and climatic conditions.

Other classic livestock anthelmintics such as macrocyclic lactones (e.g. ivermectin, selamectin, etc.), levamisole, tetrahydropyrimidines (e.g. pyrantel, morantel) and piperazine derivatives are not effective at all against Mesocestoides species or whatever tapeworms.

So far there are no antiparasitic medicines for external use such as shampoos, soaps, sprays, powders, insecticide-impregnated collars, etc. that control established tapeworm infections.

There are so far no vaccines against Mesocestoides tapeworms. To learn more about vaccines against parasites of livestock and pets click here.

Biological control of Mesocestoides (i.e. using its natural enemies) is so far not feasible.

You may be interested in an article in this site on medicinal plants against external and internal parasites.

Resistance of Mesocestoides spp to anthelmintics

So far there are no reports on resistance of Mesocestoides tapeworms to anthelmintics.

This means that if an anthelmintic fails to achieve the expected efficacy against this parasite, chance is very high that it is not due to resistance, but either the product was used incorrectly, or it was unsuited for the control of this parasite. Incorrect use is the most frequent reason for failure of antiparasitic drugs.

|

Ask your veterinary doctor! If available, follow more specific national or regional recommendations for Mesocestoides control. |