Ancylostoma is a genus of parasitic roundworms that belongs to the particular group of hookworms. They are called hookworms because they have a hook-like shape. Depending on the species, Ancylostoma worms have dogs, cats, humans and other mammals as final hosts.

The most relevant veterinary species are:

- Ancylostoma caninum, the dog hookworm, infects dogs and other canids (foxes, wolves, coyotes, etc.) worldwide. Occasionally it also infects cats and humans.

- Ancylostoma braziliense infects dogs, cats, wild canids and occasionally also humans. It is found in tropical and subtropical regions of America, including the southern United States, but also in some tropical regions of Asia.

- Ancylostoma tubaeforme, the cat hookworm, is a specific parasite of cats and is found worldwide.

- Ancylostoma ceylanicum infects mainly wild carnivores in Asia and parts of America, but can occasionally infect dogs.

The disease caused by Ancylostoma hookworms is called ancylostomiasis (or anchylostomiasis, or ankylostomiasis).

Ancylostoma hookworms do not affect cattle, sheep, pigs, horses or poultry.

Are dogs or cats infected with Ancylostoma worms contagious for humans?

YES. But not through direct contact with the animals or their feces, but mostly while walking barefoot in a place infected with Ancylostoma larvae (gardens, backyards, etc.). For additional information read the chapter below on harm caused by Ancylostoma.

There are other hookworms species, mainly Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus, which are specific human parasites and much more harmful than those hookworm species that affect dogs and cats. Neither dogs nor cats transmit these human hookworms.

You can find additional information in this site on the general biology of parasitic worms and/or roundworms.

Final location of Ancylostoma spp

Predilection site of adult Ancylostoma worms is the small intestine, but migrating larvae can be found in the skin, in the circulatory system, the lungs, the trachea (windpipe) and the bronchial tubes.

Anatomy of Ancylostoma spp

Adults of Ancylostoma are rather small worms, 5 to 15 mm long and only 0.5 mm wide, whereby males are smaller than females. They have the typical slender shape of worms, with thinner head and tail, but the head is usually bent, which makes them look like a hook. They show a whitish-pinkish color, rather reddish if they have recently fed blood. The worm's body is covered with a cuticle, which is flexible but rather tough.

The worms have no external signs of segmentation. They have a tubular digestive system with two openings. The mouth capsule has three sets of teeth used for cutting the gut's wall tissues for bloodsucking. They also have a nervous system but no excretory organs and no circulatory system, i.e. neither a heart nor blood vessels. The female ovaries are large and may contain up to 30 million eggs. Males have simple chitinous spicules for attaching to the female during copulation.

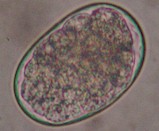

The eggs have an ovoid shape and a thin wall, measure about 40x65 micrometers, and contain already 4 to 16 cells when shed with the feces

Life cycle and biology of Ancylostoma spp

Ancylostoma worms have a direct life cycle, with dogs, cats and other carnivores as final hosts, but more complex than other roundworms with direct life cycles.

Eggs shed with the feces complete development to L2 larvae inside the egg in 2 to 9 days after shedding. Young larvae hatch and complete development to infective L3 larvae in the environment. They can swim in the humidity that covers the vegetation, where they wait for a suitable host. By cool and humid weather they can survive for weeks. Survival is much shorter in a dry environment or by hot weather.

The larvae infect the final hosts through the mouth (after ingestion of contaminated water, food or soil) or through the skin.

Some ingested larvae reach the gut, attach and complete development to adult worms. Other larvae penetrate the gut's wall and undertake a migration through various organs that brings them to the lungs, the windpipe (trachea) and the mouth, where they are again swallowed. These larvae than reach the gut, complete development to adults, attach to the gut's wall and start producing eggs.

Larvae that penetrate the skin (often between the footpads) reach a blood vessel and are carried to the lungs, from where they reach the windpipe (trachea), the mouth and are subsequently swallowed. These larvae reach the intestine, complete development to adults, attach to the gut's wall and start producing eggs.

In transport hosts (often small rodents such as rats, mice, etc.) the ingested larvae migrate to various organs where they encyst without completing development. If a dog, a cat or another suitable final host ingests such infected rodents, after digestion these larvae will go directly to the gut where they complete development to adults and start producing eggs.

Intrauterine infection of fetuses is also possible. In pregnant animals, some of the migrating larvae may get into the placenta and cross it to infect the fetus. They reach the liver of the fetus, where they remain until birth. Afterwards they migrate to the lungs, the trachea and the mouth, are swallowed and attach to the gut's wall to complete development. Some larvae can also reach the mammary glands and infect lactating animals.

The shortest prepatent period (time between infection and shedding of first eggs in the feces) is 2 to 4 weeks, much longer in case of somatic larval migration.

Harm caused by Ancylostoma infections, symptoms and diagnosis

Ancylostoma infections are particularly damaging for dogs. Adult worms in the gut are voracious bloodsuckers and change frequently the site, up to six times a day. They produce anticoagulants that prevent blood clotting. When they leave the place to bite elsewhere the bleeding continues. A single worm can consume up to 0.1 ml blood within 24 hours. 100 worms consume up to 10 ml just in one day and leave about 600 injuries that continue bleeding.

A few worms in healthy adult animals may remain asymptomatic. But heavy infections cause hemorrhage and anemia due to blood loss that can be substantial, even fatal. Dark and bloody diarrhea and vomiting are often observed, as well as pale mucosae (mucous membranes, e.g. the gums), weakness, apathy, and dull dry furr.

Migrating larvae can cause skin inflammation (dermatitis) at the points of entry that can become infected with secondary bacteria. Allergic reactions can also occur along the migration paths. Damage to the lungs causes coughing and can lead to pneumonia.

Larvae of these Ancylostoma species that infect dogs and cats can occasionally infect humans through the skin, especially if walking barefoot on infected places (gardens, backyards, etc.). The larvae get into the skin and start migrating, causing a disease called cutaneous larva migrans. The migration paths are often visible from outside as red lines under the skin. They can be quite itchy. Sometime they break open and become infected with secondary bacteria. These larvae usually die spontaneously with a few weeks. Very occasionally they can reach the lungs, other organs or the muscles. The specific human hookworms previously mentioned (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus) are substantially more harmful than their veterinary relatives.

Diagnosis requires microscopic examination of fecal samples. However, these worms can cause significant harm before egg shedding begins, especially in puppies and kittens, which can even die before eggs are shed. The number of eggs found in the feces is not indicative of the number of worms that infect the animal, because it is known that the females produce fewer eggs if they are very numerous.

Prevention and control of Ancylostoma infections

It is highly advisable to prevent pets from eating or licking soil or other substrates potentially contaminated with eggs, but this is often very difficult to achieve. In kennels, catteries, boarding houses and the like it is essential to follow strict sanitation and disinfection of cages, boxes, and any places used by the animals. Excrements must be eliminated daily. Non-porous floors make disinfection easier and more effective.

Mice and rats should be controlled because they can transmit the infection to dogs and cats. But remember that most rodenticides are also toxic for pets!

Puppies and kittens younger than 3 months should be periodically treated with a wormer approved for hookworm control. The periodicity depends on the risk of exposure, environment, etc, and must be determined by your veterinary doctor

Based on the local epidemiological situation and the pet's specific environment (rural, urban, contact with other dogs, season, climate, etc.) it can be advisable to periodically treat adult pets of both sexes with appropriate wormers as recommended by your veterinary doctor. If available and affordable it can make sense to regularly perform a fecal examination of the dog's droppings. This is particularly important for breeding animals, whose droppings should be periodically examined: if required they have to be regularly dewormed during pregnancy.

After acquiring a new pet, young or adult, it is highly advisable to perform a fecal examination and preventatively deworm it if required. If possible, whatever clinical information should be obtained from the previous owner.

All these measures are especially important in families with young children in close contact with dogs or puppies. In addition children must be instructed to frequently clean their hands with soap before eating, and not to walk barefoot outdoors on places that could be infected with larvae of these worms (gardens, yards, etc).These measures are obviously very advisable for adults as well. On the other side it is also important to train the pets not to defecate in places where the children use to play.

There are numerous anthelmintic products (also called wormers or dewormers) effective against Ancylostoma and other roundworms. They contain active ingredients of various chemical classes such as benzimidazoles (e.g. fenbendazole, febantel, flubendazole, mebendazole), tetrahydropyrimidines (e.g. pyrantel), macrocyclic lactones (e.g. milbemycin oxime, moxidectin, selamectin), emodepside, levamisole, etc. They are often used in mixtures, sometimes with specific taenicides (mostly praziquantel) to control tapeworms as well.

After deworming highly infected animals a high-protein diet and an iron supplement are often required to compensate for the blood loss. In extreme cases a blood transfusion may be indicated.

Most of these pet wormers are available in formulations for oral delivery either as solids (tablets, pills, etc.) or as liquids (drenches, suspensions, etc.). In some countries there are also a few spot-ons (= squeeze-ons = pipettes) and a few injectables that are effective against Ancylostoma hookworms.

Most wormers kill the worms shortly after treatment and are metabolized and/or excreted within a few hours or days. This means that they have a short residual effect, or no residual effect at all. As a consequence treated animals are cured from worms but do not remain protected against new infections. To ensure that they remain worm-free the pets have to be dewormed periodically, depending on age and the local epidemiological, ecological and climatic conditions.

Excepting a few spot-ons, other antiparasitics for external use (shampoos, soaps, sprays, powders, insecticide-impregnated collars, etc.) are not effective against Ancylostoma hookworms or other roundworms.

There are so far no true vaccines against Ancylostoma hookworms. To learn more about vaccines against parasites of livestock and pets click here. Dogs can actually develop a certain degree of natural immunity to Ancylostoma hookworms, which suggests that vaccination coould be feasible. And a lot of research has been actually carried out on vaccines against Ancylostoma caninum. Some experimental vaccines reached almost an 80% reduction of the worm burden. However, commercial vaccines are yet not available in most countries.

Biological control of Ancylostoma hookworms (i.e. using its natural enemies) is so far not feasible.

You may be interested in an article in this site on medicinal plants against external and internal parasites.

Resistance of Ancylostoma hookworms to anthelmintics

Resistance of Ancylostoma caninum to pyrantel has been reported in Australia and New Zealand. Resistance to fenbendazole, milbemycin oxime and pyrantel pamoate has also been reported in the USA in 2019-20.

This means that if a wormer containing the above mentioned ingredients fails to achieve the expected efficacy, it may be due to resistance. However, the experience shows that most product failures are due to incorrect use of veterinary medicines: either they are unsuited for the control of a given parasite, or they are used incorrectly.

|

Ask your veterinary doctor! If available, follow more specific national or regional recommendations for Ancylostoma control. |