Trichuris is a genus of parasitic roundworms belonging to the family Trichuridae.

belonging to the family Trichuridae.

They are found worldwide but are more abundant in regions with tropical or subtropical climate.

Prevalence varies from region to region. In endemic regions more than 50% of domestic animals can be infected.

There are several species of veterinary importance:

- Dogs: Trichuris vulpis, Trichuris campanula

- Cats: Trichuris serrata, Trichuris campanula

- Cattle, sheep, goats and other ruminants: Trichuris discolor, Trichuris globulosa, Trichuris ovis

- Pigs: Trichuris suis

Trichuris trichiura is a whipworm species parasitic of humans .

The disease caused by Trichuris whipworms is called trichuriasis.

Are animals infected with Trichuris worms contagious for humans?

- YES, but not all the species, and usually not through direct contact with the animals, but mostly through ingestion of infective eggs that contaminate the environment of infected animals (pastures, gardens, soil, sandboxes, yards, etc.). Eggs shed with the feces of infected animals are not immediately infective, but need to mature in the environment during 10 to 25 days. For additional information read the chapter below on prevention and control.

There are other worms belonging to the Trichuridae that infest pets and livestock, notably those of the genus Capillaria.

You can find additional information in this site on the general biology of parasitic worms and/or roundworms.

Final location of Trichuris worms

Predilection site of adult Trichuris worms is the large intestine (cecum and colon).

Anatomy of Trichuris worms

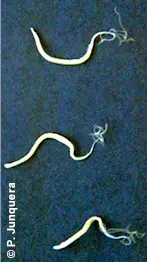

Adult Trichuris are 3 to 8 cm long and have a whitish to yellowish color. They have a characteristic shape that resembles a whip with its handle, hence their name "whipworms". The posterior end is rather thick (would be the "handle"), whereas the anterior part is longer and much thinner (would be the "whip"). Males are smaller than females.

The worm's body is covered with a cuticle, which is flexible but rather tough. The worms have no external signs of segmentation. They have a tubular digestive system with two openings. They also have a nervous system but no excretory organs and no circulatory system, i.e. neither a heart nor blood vessels. Males have only one chitinous spicule for attaching to the female during copulation.

The eggs are brownish-yellowish, about 40x70 micrometers, with a barrel-like shape, a thick membrane and typical plugs on both poles.

Life cycle of Trichuris worms

Trichuris worms have a direct life cycle. Female worms produce several thousands eggs per day. These eggs are shed with the host's feces. In the environment infective larvae develop inside the eggs in 10 to 25 days depending on temperature. These eggs are extremely resistant to cold (even frost) and dryness, and can remain infective in the soil for many years. Final hosts ingest eggs with contaminated food or water. The larvae hatch out of the eggs in the small intestine and enter the mucosa there and/or move forward to the cecum where they penetrate the mucosa and complete development to adults.

The time between infection and fist eggs shed (prepatent period) is 50 to 90 days.

Harm caused by Trichuris infections, symptoms and diagnosis

Immature larvae that penetrate the lining of the large intestine cause irritation, and blood-feeding adults damage the wall of the cecum. Nevertheless, most Trichuris infections are rather benign and cause no clinical signs. Massive infections can cause gut's inflammation (enteritis), ulceration, bleeding and subsequent anemia, bloody diarrhea, disturbed fluid absorption and dehydration, lack of appetite and weight loss. Fatalities are possible, especially in young animals, but uncommon.

Diagnosis is based on the detection of eggs in the feces. Adult worms may also be seen in the host's droppings.

Prevention and control of Trichuris infections

In livestock

Preventing whipworm infections in free ranging livestock is very difficult because Trichuris eggs can remain infective for years on pasture and are extremely resistant to adverse weather conditions. Fortunately, serious live threatening infections are uncommon. In confined livestock facilities thorough hygiene measures including manure removal are highly recommended in endemic regions.

Many anthelmintic active ingredients are effective against whipworm infections in livestock: benzimidazoles (e.g. albendazole, febantel, fenbendazole, etc.), macrocyclic lactones (e.g. doramectin, ivermectin, moxidectin). Levamisole is usually not sufficiently effective against whipworms.

These active ingredients are mainly available as drenches, slow-release boluses, injectables, feed additives or tablets, but not all formulations are available everywhere.

Excepting slow-release boluses, most wormers kill the worms shortly after treatment and are metabolized and/or excreted within a few hours or days. This means that they have a short residual effect, or no residual effect at all. As a consequence treated animals are cured from worms but do not remain protected against new infections. To ensure that they remain worm-free the animals have to be dewormed periodically, depending on the local epidemiological, ecological and climatic conditions.

In dogs and cats

To prevent whipworm infections in dogs and cats thorough daily removal of droppings is highly recommended as well as frequently changing the bedding (sawdust, sand, gravel, etc.) of playing grounds, runs, pens, cages, litter boxes, etc., especially where numerous pets live together (kennels, catteries, boarding houses, etc.). Impervious floors are less adequate for egg survival than porous ones. Young animals must be particularly protected because they are more likely to suffer from whipworm infections.

Numerous pet wormers are effective against whipworm infections, e.g. those that contain benzimidazoles (e.g. albendazole, febantel, fenbendazole, etc.), macrocyclic lactones (e.g. ivermectin, milbemycin oxime, selamectin) and emodepside. Oxantel is a tetrahydropyrimidine particularly effective against whipworms, often used in combination with pyrantel, another tetrahydropyrimidine.

Most of these pet wormers are available in formulations for oral delivery either as solids (tablets, pills, etc.) or as liquids (drenches, suspensions, etc.). In some countries a few spot-ons (= squeeze-ons = pipettes) and injectables are also available that are effective against whipworms.

Most pet wormers kill the worms shortly after treatment and are metabolized and/or excreted within a few hours or days. This means that they have a short residual effect, or no residual effect at all. As a consequence treated animals are cured from worms but do not remain protected against new infections. To ensure that they remain worm-free the pets have to be dewormed periodically, depending on age and the local epidemiological, ecological and climatic conditions.

Excepting a few spot-ons, other antiparasitics for external use on pets (shampoos, soaps, sprays, powders, insecticide-impregnated collars, etc.) are not effective against whipworms.

There are so far no true vaccines against whipworms, neither for livestock, nor for pets. To learn more about vaccines against parasites of livestock and pets click here.

Biological control of whipworms (i.e. using its natural enemies) is so far not feasible. Learn more about biological control of worms.

You may be interested in an article in this site on medicinal plants against external and internal parasites.

Eggs of Trichuris suis (affects pigs) and Trichuris vulpis (affects mainly dogs) can be infective for humans as well, but are less harmful than Trichuris trichiura, the specific human whipworm. For this reason, general hygienic measures (frequent hand washing, avoiding contact with droppings or contaminated environments, etc.) are highly recommended in endemic regions, particularly for workers in animal facilities.

Resistance of Trichuris whipworms to anthelmintics.

There are a few reports on resistance of Trichuris whipworms to anthelmintics in swine and sheep. However, this seems not to be such a serious and widespread problem as for other roundworm species (e.g. Cooperia spp, Haemonchus spp, Ostertagia spp, Trichostrongylus spp, etc.).

This means that if an anthelmintic fails to achieve the expected efficacy, it could be due to resistance. But chance is significant that either the product was unsuited for the control of Trichuris whipworms, or it was used incorrectly. Incorrect use is the most frequent cause of product failure.

Learn more about parasite resistance and how it develops.

|

Ask your veterinary doctor! If available, follow more specific national or regional recommendations for Trichuris control. |