Nematodirus is a genus of parasitic roundworms that infects cattle, sheep, goats and other domestic and wild ruminants. Worms of this genus are also called thin-necked worms or thread-necked worms.

that infects cattle, sheep, goats and other domestic and wild ruminants. Worms of this genus are also called thin-necked worms or thread-necked worms.

It is found worldwide but is more abundant in regions with temperate climate.

These worms do not affect dogs, cats or swine.

The most relevant species for livestock are:

- Nematodirus abnormalis infects mainly sheep, goats and camels; found worldwide, seldom in Africa.

- Nematodirus battus infects mainly sheep and goats; abundant in Europe and temperate North America.

- Nematodirus helvetianus infects mainly cattle; found worldwide.

- Nematodirus filicollis sheep and goats; found worldwide, seldom in Africa.

- Nematodirus spathiger infects cattle, sheep and goats; found worldwide.

The disease caused by Nematodirus worms is called nematodiriasis, nematodiriosis or nematodirosis.

Is livestock infected with Nematodirus worms contagious for humans?

- NO: The reason is that these worms are not human parasites.

You can find additional information in this site on the general biology of parasitic worms and/or roundworms.

Final location of Nematodirus worms

Predilection site of adult Nematodirus is the small intestine.

Anatomy of Nematodirus worms

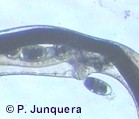

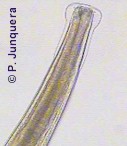

Adult Nematodirus worms are 1 to 2.5 cm long and have a whitish color, whereby females are larger than males. As in other roundworms, the body of Nematodirus worms is covered with a cuticle, which is flexible but rather tough. The tail of Nematodirus females ends in a conspicuous spine. The worms have a tubular digestive system with two openings.

Characteristic for Nematodirus worms is a swallen head preceded by a thin neck, hence their common name thin-necked worms. They also have a nervous system but no excretory organs and no circulatory system, i.e. neither a heart nor blood vessels. Males have a copulatory bursa with two thin and long spicules for attaching to the female during copulation.

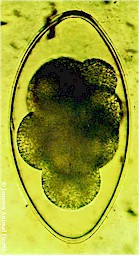

The eggs are ovoid and 70-120x130-230 micrometers, the largest among the gastrointestinal roundworms of ruminants. They have a thick shell and contain 4 to 8 cells (blastomeres) when shed in the feces, in contrast with most other gastrointestinal roundworms that contain 16 or more cells. Eggs of Nematodirus battus have a brownish color, whereas those of other species are colorless.

Life cycle of Nematodirus worms

Nematodirus worms have a direct life cycle, i.e. there are no intermediate hosts involved. Adult females lay eggs in the small intestine of the host that are shed with the feces. In contrast with many other gastrointestinal worms, once the eggs are shed the larvae remain inside the eggs where they complete development to infective larvae. This makes them very resistant to cold and dryness: they can survive very cold winters. Development to infective larvae can be completed in 2 to 4 weeks or may take months, depending on the species and the environmental conditions.

Infective larvae may hatch quickly or remain inside the eggs until the next spring. Some species (e.g. Nematodirus battus and Nematodirus filicollis) have to be exposed to long cold periods to become able to hatch. For these species, the longer and colder the winter and early spring, the more infective larvae will contaminate the pastures. In any case, infective larvae can survive for up to 10 months on pasture.

Larval development can also be completed indoors and infective larvae can survive inside animal facilities for months.

L4 larvae of some Nematodirus species (e.g. Nematodirus filicollis, Nematodirus spathiger) can stop development and remain arrested (inhibited, hypobiotic, dormant) for several months before completing development. This makes it possible for those larvae that infect hosts at the end of the summer to remain arrested inside the host during the winter and to resume development in the next spring with more favorable environmental conditions.

Livestock becomes infected after eating pasture contaminated with infective larvae, inside or outside the eggs, depending on the species and the time of the year. Ingested larvae reach the small intestine where the complete development to adult worms and begin producing eggs.

The prepatent period (time between infection and first eggs shed) is 2 to 4 weeks (without dormancy).

Harm caused by Nematodirus worms, symptoms and diagnosis

Nematodirus worms are not the most harmful among the gastrointestinal roundworms that affect livestock. However, Nematodirus battus can be particularly pathogenic for lambs. Larvae are the most damaging stage. They feed on the tissue of the gut's wall, which can be seriously damaged in case of massive infections. This causes strong diarrhea (dark, green or yellow) and dehydration. If left untreated many lambs may die (10% or more), even before having shed eggs, because the larvae had no time to complete development to adult worms.

Calves infected with Nematodirus helvetianus or Nematodirus spathiger may also become sick after massive infections, but fatalities are seldom.

Chronic infections may result in reduce weight gains, loss of appetite, etc. and worsen the damage caused by other concomitant species (e.g. Cooperia spp, Haemonchus spp, Ostertagia spp, Trichostrongylus spp, etc.).

Diagnosis is based on the clinical signs and confirmed after detection of characteristic eggs in the feces. However, as already mentioned, lambs can become seriously sick before larvae have completed development to adults, i.e. before the onset of egg production.

Prevention and control of Nematodirus infections

Preventative measures that reduce the contamination of pastures with infective larvae (e.g. pasture rotation) and reduce the risk the animals become infected can reduce the damage caused by Nematodirus and other gastrointestinal worms. This is particularly urgent for this parasite because resistance to almost all available anthelmintics is now widespread in many regions. Such preventative measures are the same for all gastrointestinal roundworms and are explained in a specific article in this site (click here).

Systematic and thorough removal of all manure, keeping the facilities dry and additional hygienic measures of animal facilities will reduce the risk that housed livestock becomes infected.

Livestock exposed to these worms often develop natural resistance progressively and may recover spontaneously. Such resistant animals do not become sick if re-infected, but continue shedding eggs that contaminate their environment. Some indigenous livestock breeds may show a high natural resistance to these worms. Unfortunately such breeds are often not the most productive ones and thus not appreciated by most farmers for economic reasons.

Numerous broad spectrum anthelmintics are effective against adult worms and larvae, e.g. several benzimidazoles (albendazole, febantel, fenbendazole, oxfendazole, etc.), levamisole, as well as several macrocyclic lactones (e.g. abamectin, doramectin, eprinomectin, ivermectin, moxidectin). But not all of them are effective against immature stages and/or arrested larvae. Read the product label carefully to find it out.

Numerous commercial products contain mixtures of two or even more active ingredients of different chemical classes. This is done to increase the chance that at least one active ingredient is effective against gastrointestinal worms that have become resistant, or to delay resistance development by those worms that are still susceptible.

Depending on the country most of these anthelmintics are available for oral administration as drenches, feed additives and/or tablets. Levamisole and most macrocyclic lactones are usually also available as injectables. A few active ingredients are also available for livestock as pour-ons and slow-release boluses.

Excepting slow-release boluses, most wormers containing benzimidazoles (e.g. albendazole, febantel, fenbendazole, oxfendazole, etc.), levamisole, tetrahydropyrimidines (e.g. morantel, pyrantel) and other classic anthelmintics kill the worms shortly after treatment and are quickly metabolized and/or excreted within a few hours or days. This means that they have a short residual effect, or no residual effect at all.

As a consequence treated animals are cured from worms but do not remain protected against new infections. To ensure that they remain worm-free the animals have to be dewormed periodically, depending on the local epidemiological, ecological and climatic conditions. An exception to this are macrocyclic lactones (e.g. abamectin, doramectin, eprinomectin, ivermectin, moxidectin), that offer several weeks protection against re-infestation, depending on the delivery form and the specific parasite.

In numerous countries monepantel, an anthelmintic of a new chemical class, has become available as a drench for use on sheep. It is effective against all Nematodirus strains that have developed resistance to other anthelmintics. It controls adult worms and L4 larvae but not inhibited larvae. Unfortunately it is not yet available in many countries and it is not approved for cattle.

So far no really effective vaccine is available against Nematodirus worms. To learn more about vaccines against parasites of livestock and pets click here.

Biological control of Nematodirus worms (i.e. using its natural enemies) is so far not feasible. Learn more about biological control of worms.

You may be interested in an article in this site on medicinal plants against external and internal parasites.

Resistance of Nematodirus to anthelmintics

There are reports on confirmed resistance of Nematodirus worms, mainly to benzimidazoles (albendazole, febantel, fenbendazole, oxfendazole, etc) in sheep and goats. But the resistance problems are not that critical and widespread as for Haemonchus worms.

This means that if an anthelmintic fails to achieve the expected efficacy against Nematodirus worms, there is a real risk that it is due to resistance to anthelmintics, particularly in sheep and goats.

Learn more about parasite resistance and how it develops.

|

Ask your veterinary doctor! If available, follow more specific national or regional recommendations for Nematodirus control. |